Mount Saint Vincent University (MSVU) Art Gallery

Mount Saint Vincent University (MSVU) Art Gallery

Learning Space

Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery in Nova Scotia (in partnership with Eyelevel Gallery) presented a travelling exhibition organized and circulated by Truck Contemporary Art, Calgary, entitled “Taskoch pipon kona kah nipa muskoseya, nepin pesim eti pimachihew/Like the Winter Snow Kills the Grass, the Summer Sun Revives.” This exhibition of artistic works by seven contemporary Indigenous artists from across Canada aimed “to address and initiate a discussion on how Indigenous languages intertwine with Indigenous epistemologies and how the dormancy and extinction of Indigenous languages leads to a hindrance of culture and knowledge” (https://www.msvuart.ca/exhibition/pipon-kona-nepin-pesim/). Please visit the MSVU art gallery website to learn more.

Espace d’apprentissage

Galerie d’Art de l’Université Mount Saint Vincent en Nouvelle-Écosse (une partenaire de Eyelevel Gallery) a présenté une exposition itinérante organisée et diffusée par Truck Contemporary Art, Calgary, intitulée « Taskoch pipon kona kah nipa muskoseya, nepin pesim eti pimachihew / Like the Winter Snow Kills the Grass, the Summer Sun Revives » [fr. Comme la neige d’hiver tue l’herbe, le soleil d’été la ravive]. Cette exposition d’œuvres artistiques de sept artistes autochtones contemporains de partout au Canada visait « à aborder et à lancer une discussion sur la façon dont les langues autochtones s’entremêlent avec les épistémologies autochtones et comment l’hibernation et l’extinction des langues autochtones conduisent à un frein de la culture et des connaissances » (https://www.msvuart.ca/exhibition/pipon-kona-nepin-pesim/). Veuillez visiter le site web de la galerie d’art MSVU pour en savoir plus.

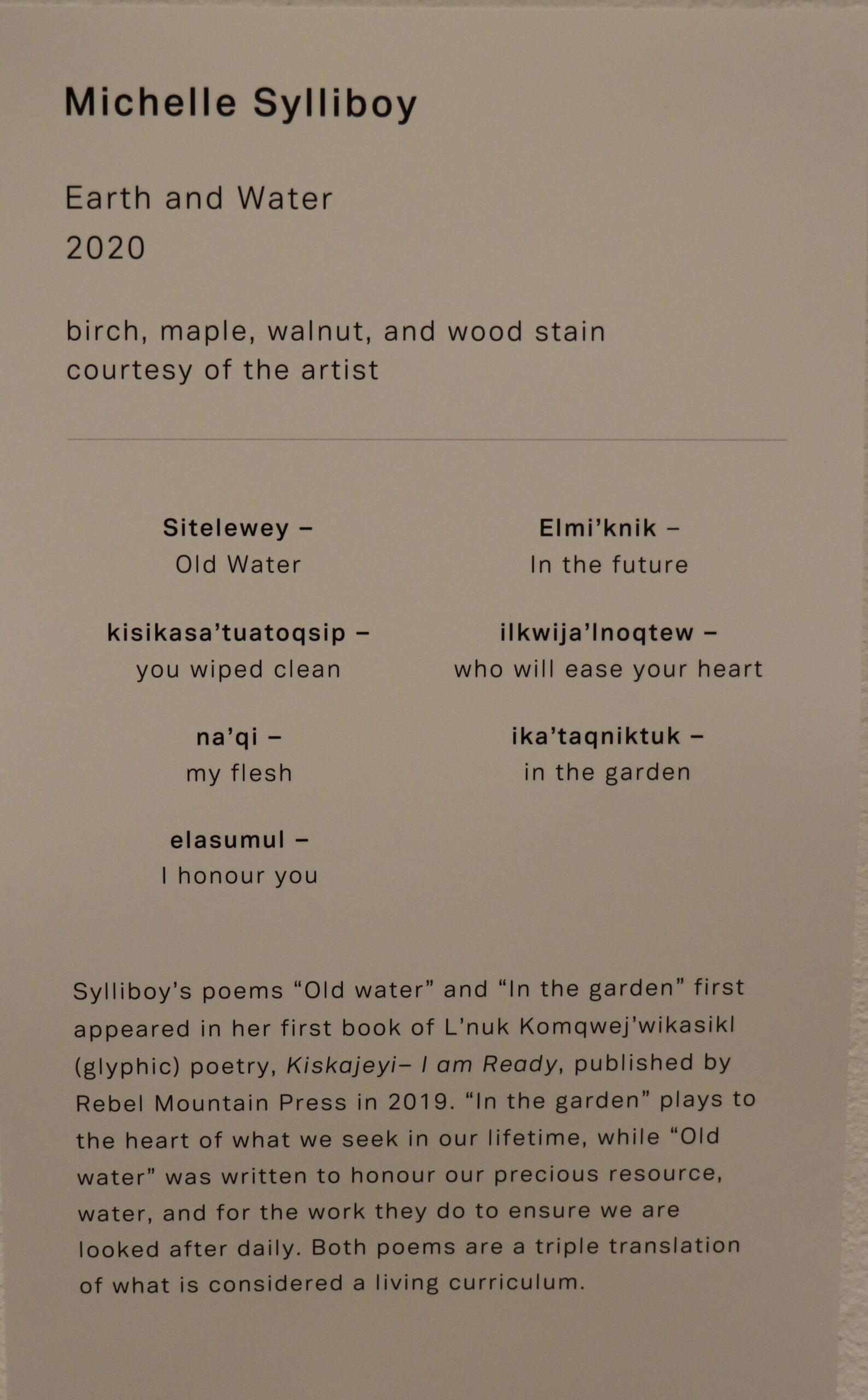

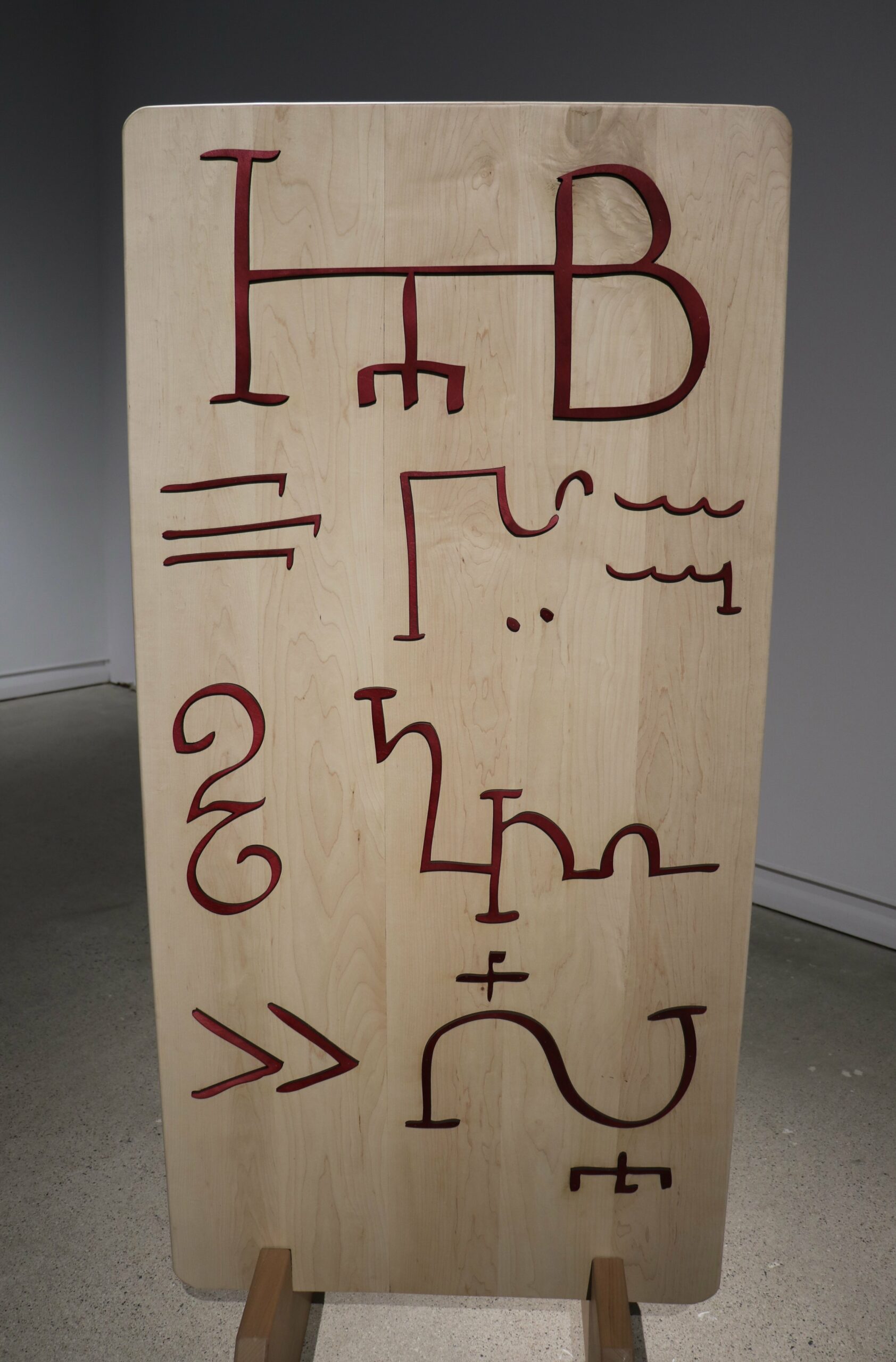

Earth and Water, Michelle Sylliboy

This artwork celebrates Indigenous languages and the power of poetry. “Old Water,” a stunning collection of carved wooden planks, invites the gallery visitors to immerse themselves in the beauty of Indigenous words and the profound message they convey.

The artwork features a poignant poem entitled, “Old Water,” carved into walnut, birch, and maple wood planks. The words read: “old water / you wiped clean / my flesh / I honour you / In the future / who will ease your heart / in the garden.” This poem pays homage to the essential element of water while echoing the deep connection between nature and humanity.

Through intricate woodcarving techniques, the artist skillfully transforms each plank into a visual representation of Indigenous languages’ resilience and significance. The organic textures of walnut, birch, and maple wood serve as a canvas for the written word, creating a harmonious fusion of art, literature, and nature.

In exploring the concepts of the multilingual subject and the authentic speaker, Blyth (2018) writes, “The linguistic performance of one’s identity can be framed either in terms of conforming to external sociolinguistic norms or as an internal process of self-authentication” (p. 63). This artwork, using natural material to display the poem and the artist’s connection to nature and land, provides a deep contemplation on the value of preserving and revitalizing Indigenous languages and, thus, Indigenous identities and histories.

Terre et Eau, Michelle Sylliboy

Cette œuvre célèbre les langues autochtones et le pouvoir de la poésie. « Old Water », une magnifique collection de planches de bois sculptées, invite les visiteurs de la galerie à se plonger dans la beauté des mots autochtones et le message profond qu’ils transmettent.

L’œuvre présente un poème poignant intitulé « Old Water » [Vieille Eau], sculpté dans des planches de noyer, de bouleau et d’érable. Les mots disent : « vieille eau / tu as nettoyé / ma chair / je te rends hommage / dans le futur / qui apaisera ton cœur / dans le jardin. » Ce poème rend hommage à l’élément essentiel qu’est l’eau tout en évoquant la profonde connexion entre la nature et l’humanité.

À travers des techniques de sculpture sur bois complexes, l’artiste transforme habilement chaque planche en une représentation visuelle de la résilience et de la signification des langues autochtones. Les textures organiques du noyer, du bouleau et de l’érable servent de toile pour le mot écrit, créant une fusion harmonieuse de l’art, de la littérature et de la nature.

En explorant les concepts du sujet multilingue et de l’orateur authentique, Blyth (2018) écrit : « La performance linguistique de l’identité peut être encadrée soit en termes de conformité aux normes sociolinguistiques externes, soit comme un processus interne d’auto-authentification » (p. 63). Cette œuvre d’art, utilisant des matériaux naturels pour afficher le poème et la connexion de l’artiste à la nature et à la terre, offre une profonde réflexion sur la valeur de préserver et revitaliser les langues autochtones, et, par conséquent, les identités et histoires autochtones.

Michelle Sylliboy. Earth and Water, 2020 (Installation shot at MSVU Art Gallery, Halifax, NS), Birch, maple, walnut and wood stain. Courtesy of the Artist, Michelle Sylliboy. Photo Credit: Susan M. Holloway.

Michelle Sylliboy. Terre et Eau, 2020 (Photo d’installation à la Galerie d’art de l’Université Mount Saint Vincent, Halifax, Nouvelle-Écosse), bouleau, érable, noyer et teinture pour bois. Avec l’aimable autorisation de l’artiste, Michelle Sylliboy. Crédit photo : Susan M. Holloway

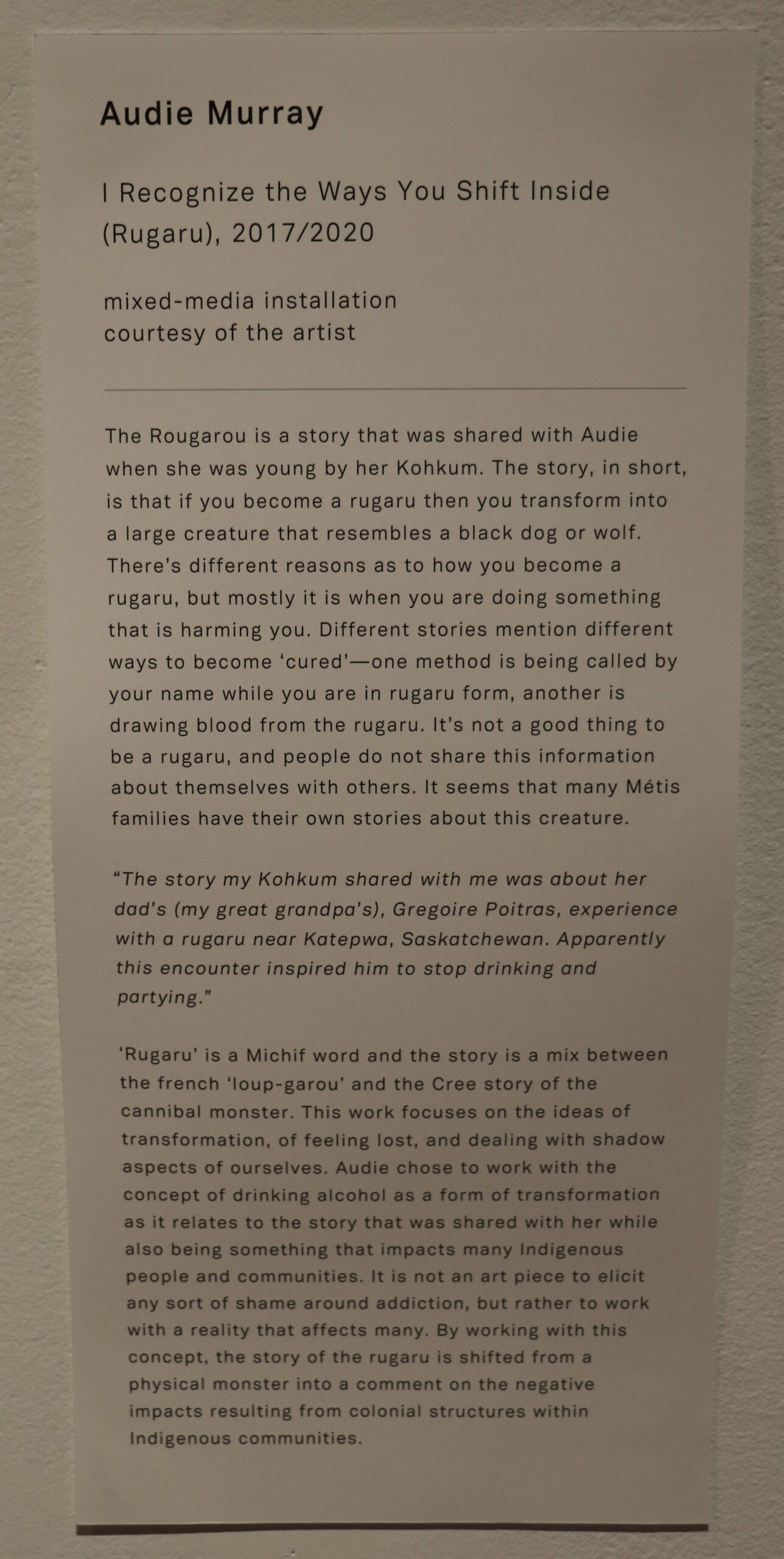

Rugaru, Audie Murray

“Rugaru: I Recognize the Ways You Shift Inside,” is an art exhibition by Audie Murray. This artwork explores the captivating story of transformation, where a person transforms into a creature resembling a large black dog or wolf; known as the rugaru, with retransformation occurring by calling out the person’s name.

At its core, the story of the rugaru symbolizes profound internal emotions and personal experiences. Murray weaves this narrative as a creative commentary on the enduring impact of colonial structures and systems on Indigenous and First Nations communities. The exhibition is a profound exploration of identity and resilience, capturing the essence of the rugaru legend as a metaphor for the complex interplay between tradition, cultural heritage, and the influences of colonial history.

When exploring inter-modal construction, Unsworth (2006) writes, “What is being investigated here is the space of integration between language and image as social semiotic systems in order to provide a theoretical description of the dynamics of interaction between language and image in meaning-making” (p. 60). Thus, in the second photograph, a viewer can see a stand, a rug, a wooden chair, and a foldable table with crushed cans on top, dried flowers adorning the wall, a hanging tapestry with the word “rugaru” embroidered onto it, and a piece of plastic tossed on the floor next to the rug. In relation to Unsworth’s explanation of the interconnection between word and image, we see the word “rugaru” and the crushed cans in connection with one another. The negative effects of drinking lead to the rugaru transformation. The first photo below, which is of an art label, explains this connection in greater detail.

This exhibition is a powerful testament to the resilience and a call for understanding the deep-rooted impact of historical trauma and ongoing struggles in Indigenous and First Nations communities.

« Rugaru : Je reconnais les façons dont tu te transformes à l’intérieur » est une exposition d’art d’Audie Murray. Cette œuvre explore l’histoire captivante de la transformation, où une personne se transforme en une créature ressemblant à un grand chien noir ou à un loup ; connu sous le nom de rugaru, avec une retransformation qui se produit en appelant le nom de la personne.

Au cœur de l’histoire du rugaru se trouve le symbole de profondes émotions internes et d’expériences personnelles. Murray fournit un commentaire créatif sur l’impact durable des structures et des systèmes coloniaux sur les communautés autochtones et des Premières Nations. L’exposition est une exploration profonde de l’identité et de la résilience, capturant l’essence de la légende du rugaru comme une métaphore de l’interaction complexe entre la tradition, le patrimoine culturel et les influences de l’histoire coloniale.

En explorant la construction intermodale, Unsworth (2006) écrit : « Ce qui est étudié ici, c’est l’espace d’intégration entre le langage et l’image en tant que systèmes sémiotiques sociaux afin de fournir une description théorique de la dynamique de l’interaction entre le langage et l’image dans la création de sens » (p. 60). Ainsi, dans la deuxième photographie, un spectateur peut voir un support, un tapis, une chaise en bois et une table pliante avec des canettes écrasées dessus, des fleurs séchées ornant le mur, une tapisserie suspendue avec le mot « rugaru » brodé dessus, et un morceau de plastique jeté au sol à côté du tapis. En relation avec l’explication d’Unsworth sur l’interconnexion entre le mot et l’image, nous voyons le mot « rugaru » et les canettes écrasées en relation l’un avec l’autre. Les effets négatifs de la consommation d’alcool conduisent à la transformation en rugaru. La première photo ci-dessous, qui est une étiquette artistique, explique cette connexion plus en détail.

Cette exposition est un puissant témoignage de la résilience et un appel à comprendre l’impact profondément enraciné du traumatisme historique et des luttes continues dans les communautés autochtones et des Premières Nations.

Audie Murray. I Recognize the Ways You Shift Inside (Rugaru) 2017/2020 (Installation shot at MSVU Art Gallery, Halifax, NS), mixed-media installation. Courtesy of the Artist, Audie Murray. Photo Credit: Susan M. Holloway.

Audie Murray. Je reconnais les façons dont tu te transformes à l’intérieur (Rugaru) 2017/2020 (Photo d’installation à la Galerie d’art de l’Université Mount Saint Vincent, Halifax, Nouvelle-Écosse), installation multimédia. Avec l’aimable autorisation de l’artiste, Audie Murray. Crédit photo : Susan M. Holloway.

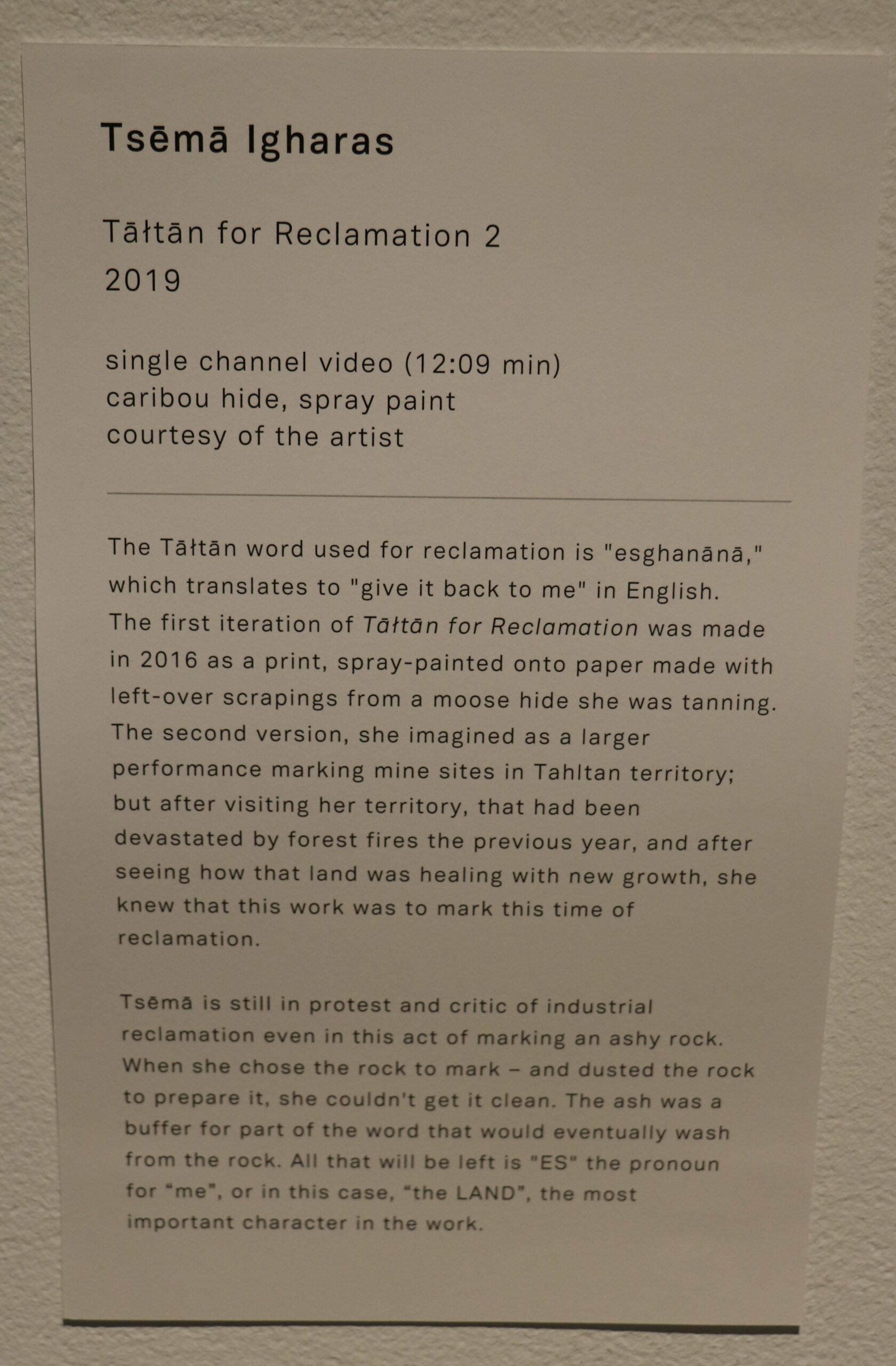

Tattan* for Reclamation 2, Tsema Igharas

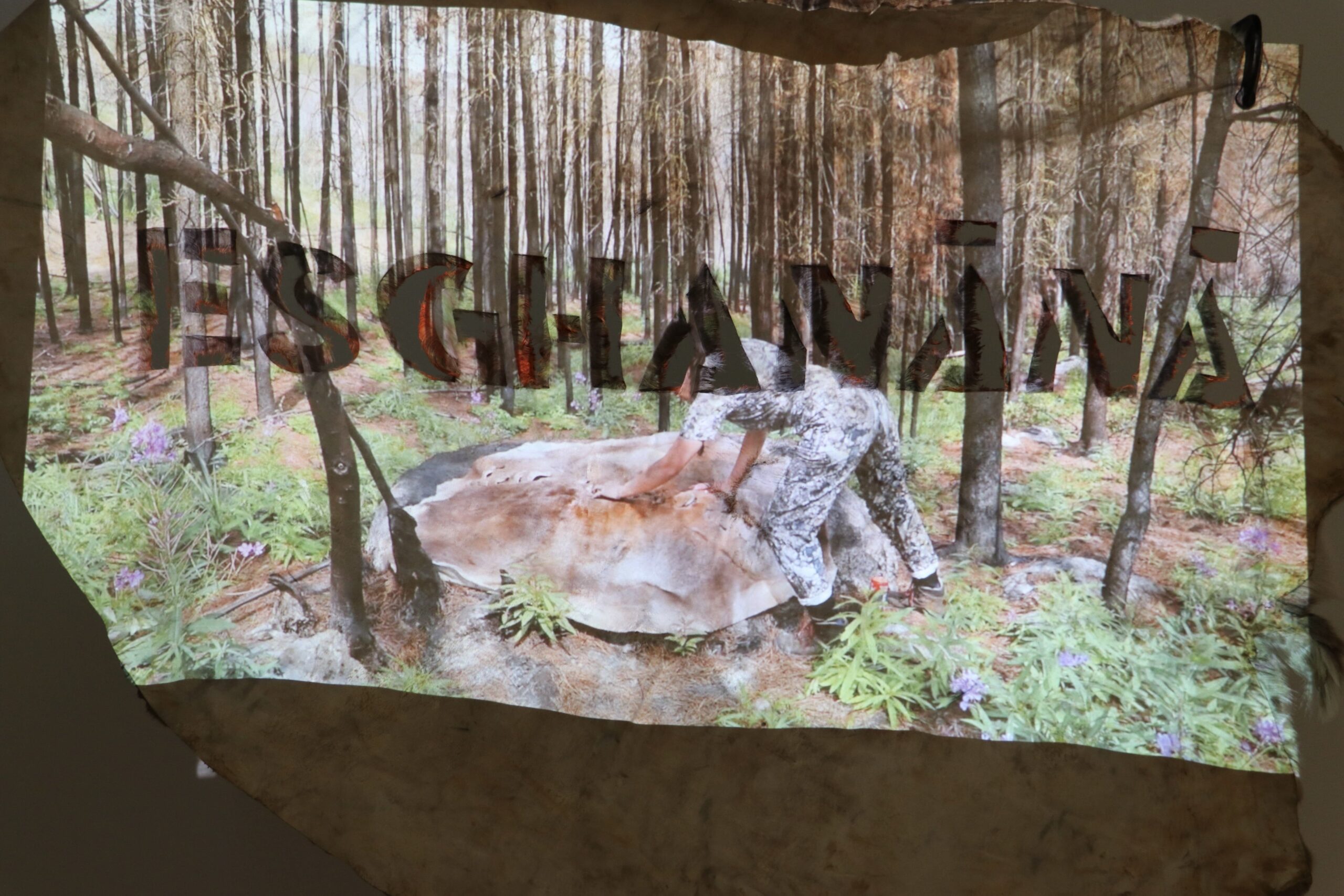

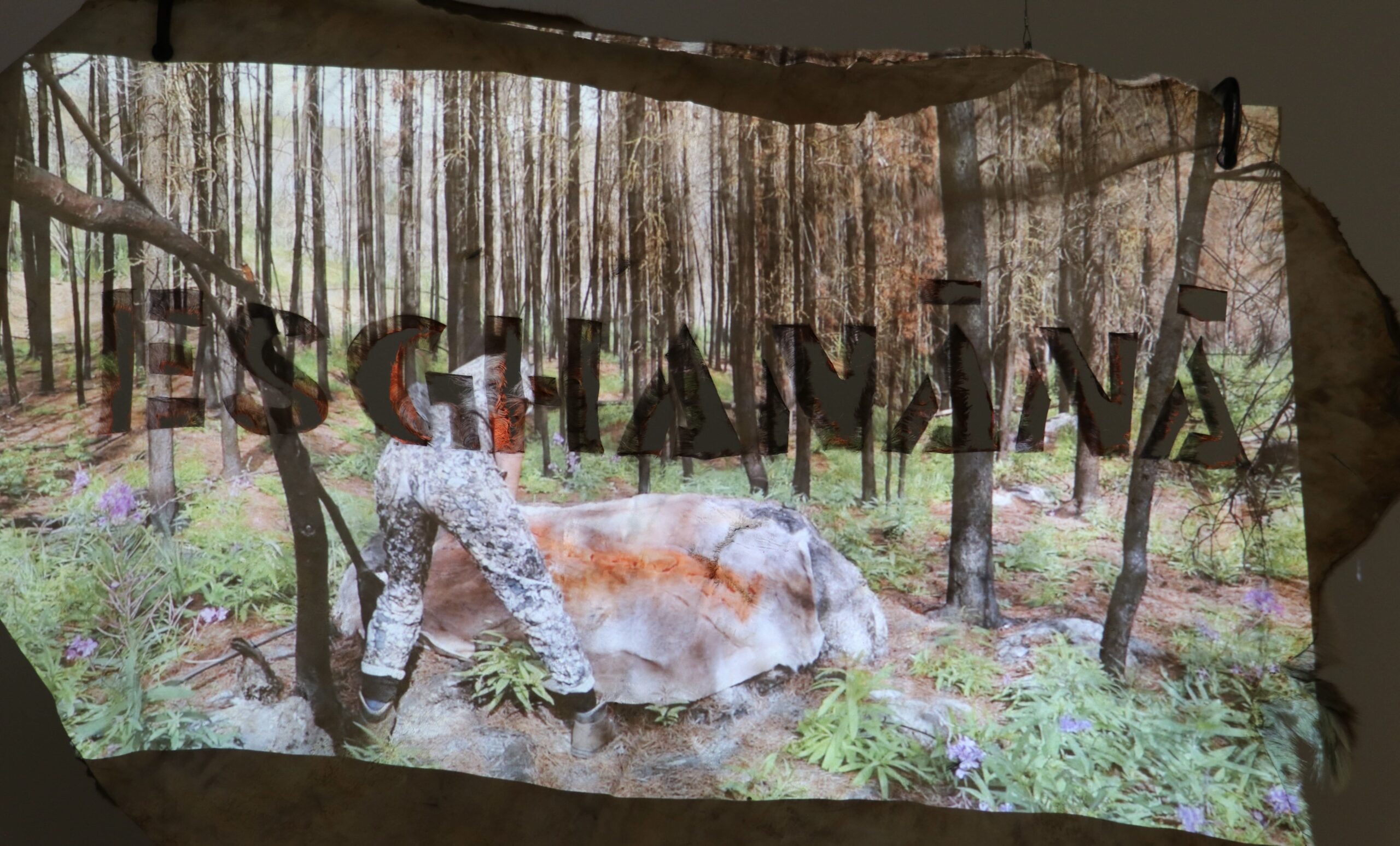

This artwork stands as a powerful testament to love for territory and land, intertwining Indigenous language, a heartfelt plea, and the symbolic presence of caribou hide.

At the heart of “Tattan” lies the word “reclamation,” expressed in the Indigenous language as “esghanana,” which translates to “give it back to me.” This plea is Tsema’s passionate and artistic response to the devastating forest fires that threaten the lands of the Tahltan territory. Unsworth (2006) writes, “Language is considered as a meaning-making system where the options available to individuals to achieve their communicative goals are influenced by the nature of the social context and how individuals are positioned in relation to it” (p. 57). Tsema, in the artwork photographed below, (re)designs animal hide to make connections between marginalized Indigenous languages to make connections and establish ties between language, animals, land, and art to develop further the concept of what was lost throughout colonial history.

The work of art showcases a 12-minute video, thoughtfully curated, that reveals the intricate process of creating the print from the caribou hide. The video offers a glimpse into the artist’s meticulous artistry. The centrepiece of the exhibition features an art piece crafted from caribou hide, symbolizing the deep connection between Indigenous communities and the land. Similarly to Unsworth’s mention of language and a person’s social relation to language, Tsema’s video presents the methods behind (re)designing the caribou hide to serve as a print. As the artwork unfolds, the caribou hide takes on a luminous quality, illuminated by a gentle light that shines behind it, displaying the word “esghanana” reflected on a wall in front of the hide.

Tattan* pour la Réclamation 2, Tsema Igharas

Cette œuvre d’art est un puissant témoignage d’amour pour le territoire et la terre, entrelaçant la langue autochtone, une supplication sincère et la présence symbolique de la peau de caribou.

Au cœur de « Tattan » se trouve le mot « réclamation », exprimé dans la langue autochtone comme « esghanana », qui se traduit par « rendez-le moi ». Cette supplication est la réponse passionnée et artistique de Tsema aux incendies de forêt dévastateurs qui menacent les terres du territoire Tahltan. Unsworth (2006) écrit : « La langue est considérée comme un système de création de sens où les options disponibles pour les individus afin d’atteindre leurs objectifs communicatifs sont influencées par la nature du contexte social et la manière dont les individus y sont positionnés » (p. 57). Tsema, dans l’œuvre d’art photographiée ci-dessous, (re)conçoit la peau d’animal pour établir des liens entre les langues autochtones marginalisées, et créer des connexions et des liens entre la langue, les animaux, la terre et l’art pour développer davantage le concept de ce qui a été perdu tout au long de l’histoire coloniale.

L’œuvre d’art présente une vidéo de 12 minutes, soigneusement organisé, qui révèle le processus complexe de création de l’estampe à partir de la peau de caribou. La vidéo offre un aperçu de l’art méticuleux de l’artiste. La pièce maîtresse de l’exposition présente une œuvre d’art fabriquée à partir de peau de caribou, symbolisant la connexion profonde entre les communautés autochtones et la terre. De manière similaire à la mention d’Unsworth sur la langue et la relation sociale d’une personne à la langue, la vidéo de Tsema présente les méthodes de (re)conception de la peau de caribou pour servir d’estampe. Au fur et à mesure que l’œuvre d’art se déroule, la peau de caribou prend une qualité lumineuse, éclairée par une lumière douce qui brille derrière elle, affichant le mot « esghanana » réfléchi sur un mur devant la peau.

Tsēmā Igharas, Tałtan for Reclamation 2, 2019 (Installation shot at MSVU Art Gallery, Halifax, NS), single-channel video (12:09), caribou hide, spray paint. Courtesy of the Artist, Tsēmā Igharas. Photo Credit: Susan M. Holloway.

*Please find the correct spelling of the Indigenous word “Tattan” and its meaning in the photograph of the wall label (first photograph under the exhibition subheading) as it is presented at the MSVU Art Gallery accompanying this work of art. The photograph of the wall label is present directly below the subheading introducing the art exhibition.

Tsēmā Igharas, Tałtan pour la Réclamation 2, 2019 (Photo d’installation à la Galerie d’art de l’Université Mount Saint Vincent, Halifax, Nouvelle-Écosse), vidéo à canal unique (12:09), peau de caribou, peinture en aérosol. Avec l’aimable autorisation de l’artiste, Tsēmā Igharas. Crédit photo : Susan M. Holloway.

*Veuillez trouver l’orthographe correcte du mot autochtone « Tattan » et sa signification sur l’étiquette murale (première photo sous le sous-titre de l’exposition) telle qu’elle est présentée à la Galerie d’art de l’Université Mount Saint Vincent accompagnant cette œuvre d’art. La photo de l’étiquette murale est directement sous le sous-titre introduisant l’exposition d’art.

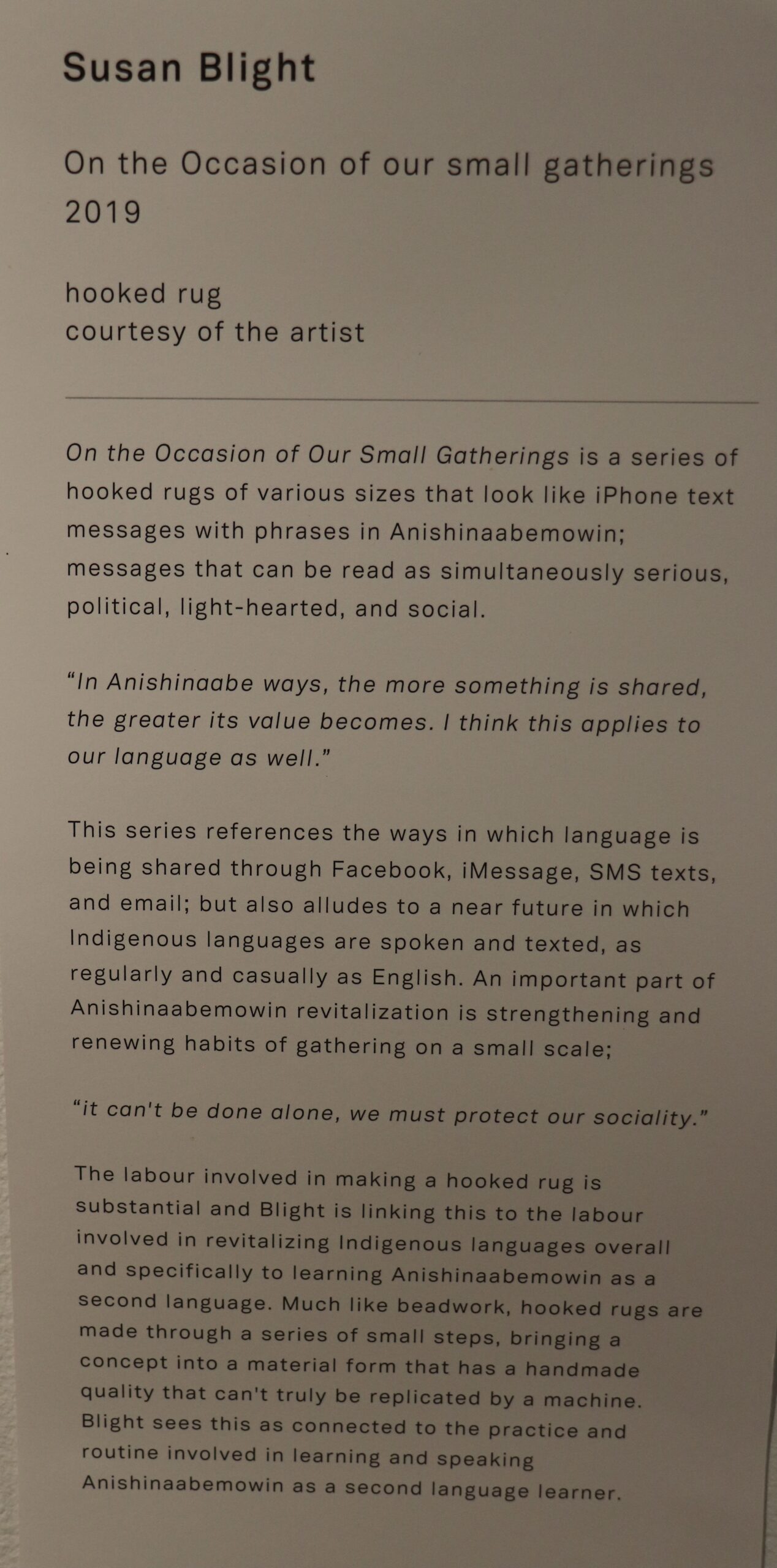

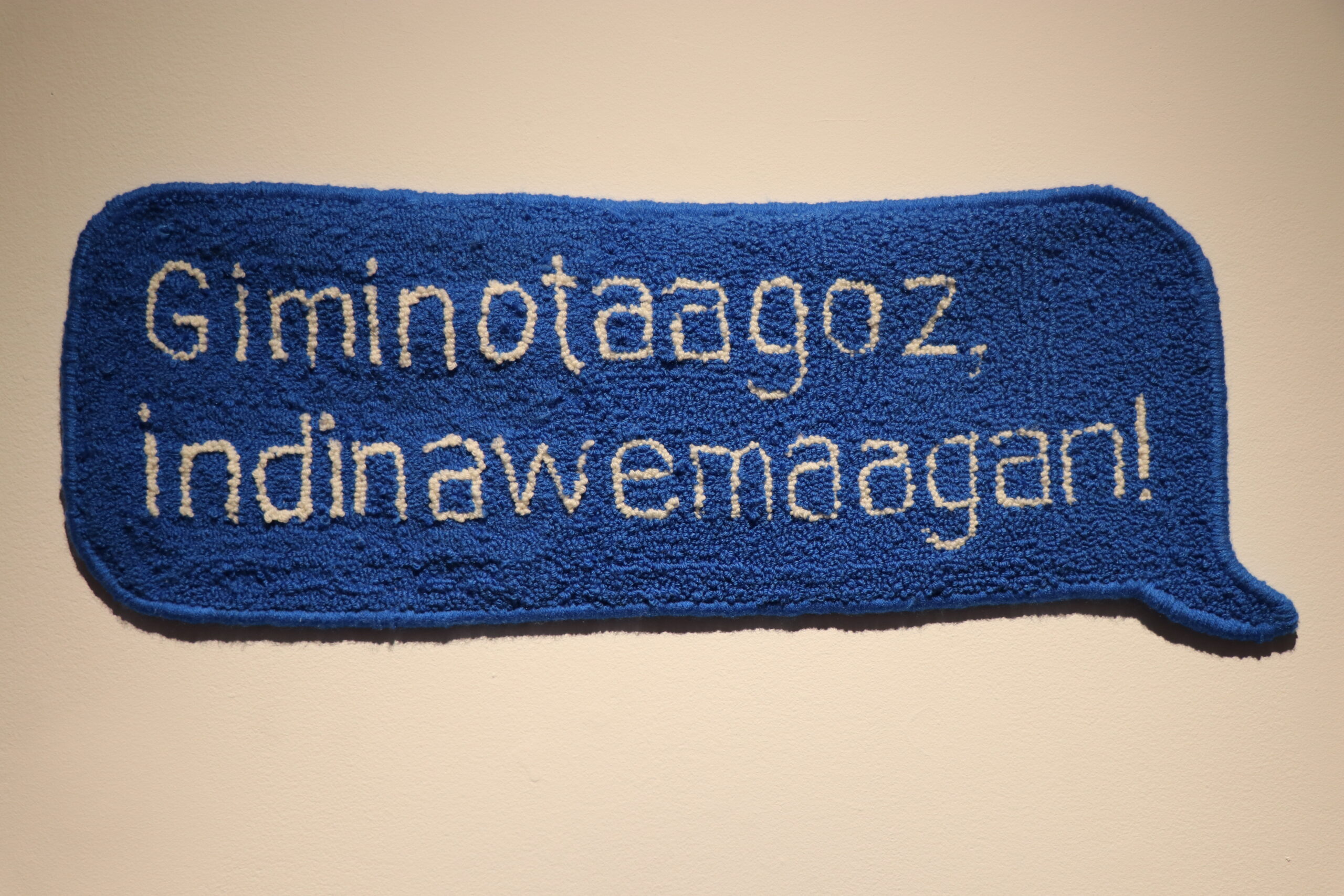

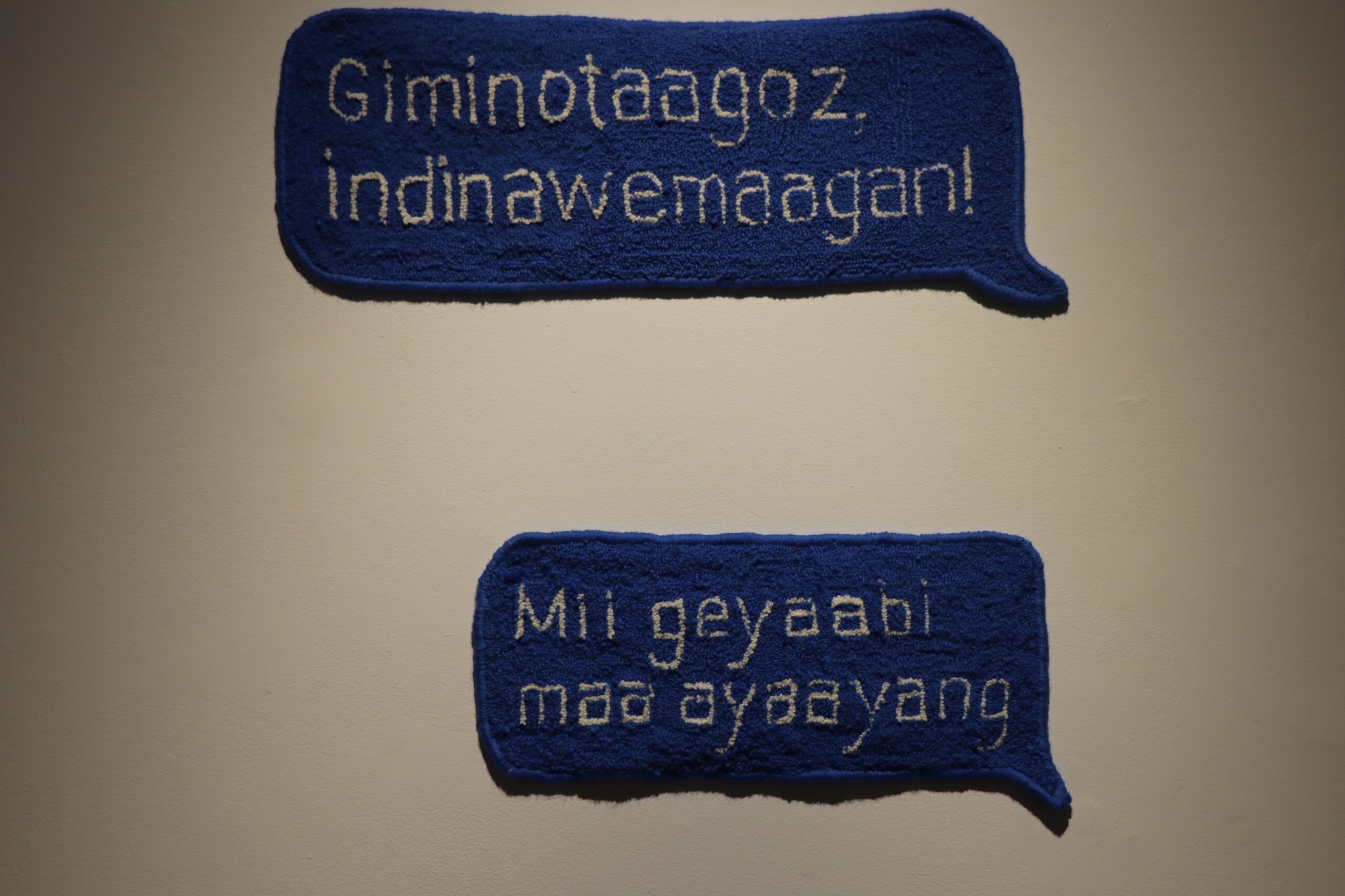

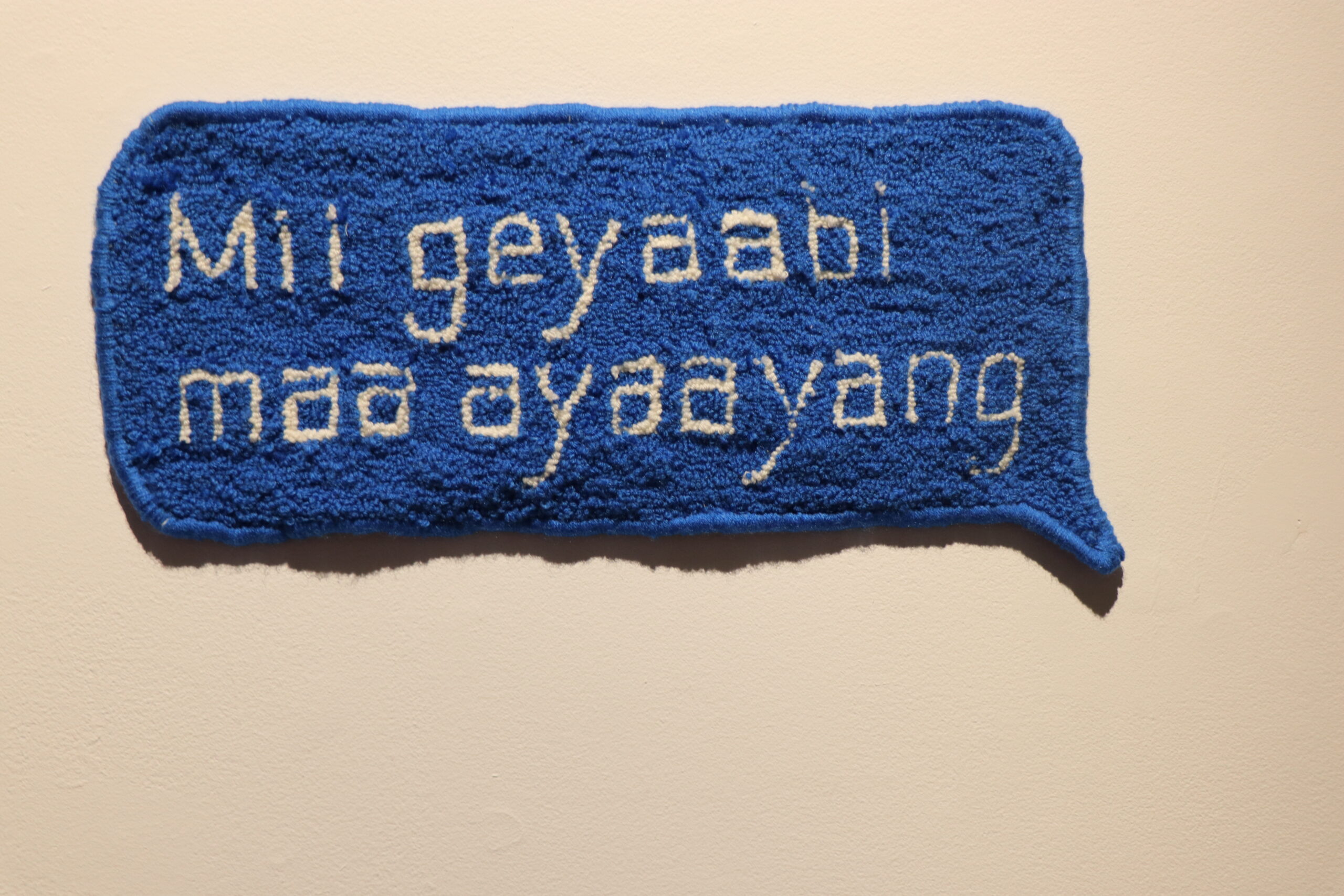

Susan Blight, Hooked Rug Exhibition

The “Hooked Rug Exhibit” by Susan Blight shows where the art of rug-making intertwines with the beauty of Indigenous language. Susan presents a visionary perspective through a series of carefully crafted hooked rugs, envisioning a future where Indigenous languages thrive and find expression in modern technologies.

In this artwork, Blight uses hooked rugs in varying sizes to recreate iPhone text messages, all written and sent in Anishinaabemowin – the language of the Anishinaabe people. This artwork serves as an ode to Indigenous language, representing the hope for a future where Indigenous languages are used as regularly as English in text messaging and various other methods of communication. In writing about minority languages in a predominantly English-speaking county, Taylor et al. (2008) urge educators to view “identity and literacy as transnational and transcultural trajectories rather than static inventories of traits and capacities: identity and literacy might be redefined as social practices and dynamic relationships that emerge through transnational forms of community, mobility, communication and cultural expression that articulate multiple global contexts” (p. 271). Blight’s artwork and hope for a future of inclusivity in modern modes of communication (i.e. iMessaging) allows us to see the possibility of Indigenous and First Nations languages being included in what is readily available to dominant languages.

Blight shares her vision where Indigenous languages not only survive but flourish in a contemporary landscape, becoming available and seamlessly woven into communication technologies. Blight’s hooked rugs showcase the possibility of that vision.

Susan Blight, Exposition de tapis crochetés

L’exposition « Hooked Rug » [tapis crocheté] de Susan Blight montre comment l’art du tapis crocheté s’entrelace avec la beauté de la langue autochtone. À travers une série de tapis crochetés soigneusement confectionnés, Susan présente une perspective visionnaire, envisageant un avenir où les langues autochtones prospèrent et s’expriment dans les technologies modernes.

Dans cette œuvre, Blight utilise des tapis crochetés de tailles variées pour recréer des messages texte d’iPhone, tous écrits et envoyés en Anishinaabemowin, la langue du peuple Anishinaabe. Cette œuvre sert d’ode à la langue autochtone, représentant l’espoir d’un avenir où les langues autochtones sont utilisées aussi régulièrement que l’anglais dans les messages texte et divers autres moyens de communication. En écrivant sur les langues minoritaires dans un pays principalement anglophone, Taylor et al. (2008) exhortent les éducateurs à considérer « l’identité et la littératie comme des trajectoires transnationales et transculturelles plutôt que des inventaires statiques de traits et de capacités : l’identité et la littératie peuvent être redéfinies comme des pratiques sociales et des relations dynamiques qui émergent à travers des formes transnationales de communauté, de mobilité, de communication et d’expression culturelle qui articulent de multiples contextes mondiaux » (p. 271). L’œuvre de Blight et l’espoir d’un avenir inclusif dans les modes de communication modernes (par exemple, les messages iMessage) nous permettent de voir la possibilité d’inclure les langues autochtones et des Premières Nations dans ce qui est facilement disponible pour les langues dominantes.

Blight partage sa vision où les langues autochtones ne survivent pas seulement mais prospèrent dans un paysage contemporain, devenant disponibles et intégrées de manière transparente dans les technologies de communication. Les tapis crochetés de Blight illustrent la possibilité de cette vision.

Susan Blight. On the Occasion of our small gatherings, 2019 (Installation shot at MSVU Art Gallery, Halifax, NS), hooked rug. Courtesy of the Artist, Susan Blight. Photo Credit: Susan M. Holloway.

For more information about the Mount Saint Vincent Art Gallery, please go to their website found at https://www.msvuart.ca/

Susan Blight. À l’occasion de nos petites réunions, 2019 (Photo d’installation à la Galerie d’art de l’Université Mount Saint Vincent, Halifax, Nouvelle-Écosse), tapis crocheté. Avec l’aimable autorisation de l’artiste, Susan Blight. Crédit photo : Susan M. Holloway.

Pour plus d’informations sur la Galerie d’art de l’Université Mount Saint Vincent, veuillez consulter leur site web à l’adresse suivante : https://www.msvuart.ca/